What Manolis Glezos told us

(I Thank once again Richard McAleavey for the translation of this short account of a moving encounter. And Kristien Pottie for Manolis Gllezos' photos.

First published in English in Richard McAlevey's excellent blog, Cunning Hired Knaves. )

First published in English in Richard McAlevey's excellent blog, Cunning Hired Knaves. )

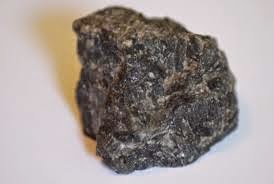

It’s an honour to be up close to a monumental figure in Europe’s history. I had such an honour recently, during a talk on debt and the policies of Syriza and Podemos on this and other questions related to the restoring of democracy, when I sat on a panel with Manolis Glezos and Eric Toussaint. Manolis Glezos is now 94 years old and the oldest member of the European Parliament. He is also one of the most active, and among those who take their role the most seriously. Manolis is a deputy for Syriza in the European Parliament. He was never a docile activist and always argued against the steps taken by the Syriza leadership that he did not agree with, based on the enormous common sense he draws from his experience of rural life, of activist life, but also from his solid training as a scientist in mineralogy. This man knows what a people is -he was mayor of his village on the island of Naxos- and he also knows what a mineral is: he showed us samples of marble and emery from his island. He also showed us, in a fabulous parable, the strength that lies in diversity, taking as his example emery, a dark rock, composed of 30 minerals, which might therefore seem fragile, but which is tougher and more resistant than diamond. He hurled it against the ground at force, and the diverse compound showed not the slightest scratch.

Manolis is famous in Greece for a feat he performed: in the midst of the Nazi occupation, when the German forces were struggling to maintain control in the face of a constant civil and military resistance from the Greek people, he climbed up the Acropolis and tore down the flag of the swastika, replacing it with the Greek flag. After this feat, all that remained for him was to join the guerrilla army of ELAS (Greek People’s Liberation Army, in Greek. This people’s army would go on to liberate Greece and defeat Hitler’s war machine, in an era full of examples of dignity. Among them, the solidarity networks set up in the face of the economic catastrophe created by the Nazis and Greek collaborators. Everyone remembers the more than 100,000 deaths from hunger in 1941, when Nazi Germany extracted a tax from Greece under the paradoxical form of an “occupation loan” under which the Greek people had to fund their own submission and exploitation. Resistance proved widespread and had epic tones, such as those demonstrations in Athens that defied the Nazi army and though they ended with dozens dead this did not prevent them from repeating, or such as the material solidarity in the distribution of the scarce food that was available. Or the popular self-organisation (people power, λαοκρατία) that ruled the large areas liberated under the co-ordination of the Mountain Government).

Manolis is a synthesis of all of this, and though he comes from a political tradition that is authoritarian and Stalinist in origin, he is a huge defender of direct democracy and of pluralism. When he was elected mayor of his village, he said to his fellow villagers who came to congratulate him and express their trust, that “I’m not the one in charge now, it is now up to you to decide”. People withdrew from him shyly, since they were not accustomed to such things: following the war and the long past experience of self-organisation during the resistance, nothing remotely similar had occurred again. There was a need to go back to learning to take direct citizen responsibility. This is what happened during one of the first minor conflicts relating to the village cemetery. According to reports from the council technicians, the cemetery, which was very close to the centre, was also too close to the sources of water used by the village and could contaminate them, and hence they recommended moving it to somewhere a bit further off. Manolis put this to the neighbours’ assembly, but one of the women present said: “if you move the village cemetery away, I will no longer be able to see my husband every morning from my window”. Other neighbours agreed with the widow and it was agreed that the cemetery would not be moved from where it was. This meant having to seek out other sources of water, but the principle of popular decision against the opinion of the mayor and the technicians had prevailed. From then on, despite the initial reluctance, it was a normal practice. Looking me in the eye and gently grabbing me by the lapel of my jacket, Manolis said to me firmly: “You call yourselves Podemos [We Can], but you have to ask yourselves: what is it you can do? Without the people and their direct participation you can do nothing.” Manolis singled out an important task for us.

Following his intervention, Manolis told an anecdote that is a veritable parable for the current situation in Greece. On one occasion, during the semi-dictatorial period that followed the Greek Civil War, he was taken prisoner by the gendarmes. He escaped for a first time from the dungeon and they arrested him again. This time, to teach him and the other communist prisoners a lesson, they let it be known that in the cell where Manolis was held there would be a guard pointing a gun at him night and day and that he would be on his knees with his hands cuffed behind his back. And this is what they did. As the first guard aimed at Manolis, Manolis said to him calmly: “You have a gun and I am unarmed. You are pointing it at me and I’m here with my hands cuffed. I suppose you think you are free and I am the prisoner, but you’re wrong.” The guard showed his surprise with this declaration and Manolis explained: “You are here because you receive orders from your superiors, but I receive orders from no-one. I am free and you are under subjection.” This gave rise to a long conversation between the two. When the shift of the next guard began, the first one said to him to wait for a moment as he wanted to finish the conversation. Finally the second guard arrives, somewhat surprised, and points the pistol at our man. Manolis begins a disquisition on the handcuffs placed on him. He explains in detail what metals they are made of, how the metals have been melted and the different pieces of which they are made up. Meanwhile, he fiddles with the cuffs until he manages to take them off. He tells the guard that he is tired and that he cannot sleep with the cuffs on: he hands them over to him and says: “I’m tired and I’m going to sleep, if you want to shoot, shoot…” The second guard did not shoot and after a while, they end up setting Manolis free. Many years later, Manolis was in Athens walking down the street and he saw a person approaching him, greeting him from afar. The unknown person said: “perhaps you’ve forgotten about me, but I know who you are: you are the man who one day told me that I was a slave when I thought I was free, and thanks to whom I am a free man.” The former prisoner and the former jailer gave each other a strong embrace.

The ancients said of Greece under Roman rule that “Graecia capta ferum captorem cepit” (Captive Greece defeated its fierce conqueror). Glezos’s anecdote operates in the same way: the dignity, wisdom and calm of decent and lucid people such as Manolis Glezos, such as Alexis Tsipras or Yanis Varoufakis, whom the world looks upon as prisoners, in the hands of their fierce and illegitimate creditors, is showing once again in the current negotiations with European partners and EU institutions just who is the free person and who is the slave.